Versions in عربي (Arabic), 中文 (Chinese), Français (French), 日本語 (Japanese), Русский (Russian), and Español (Spanish)

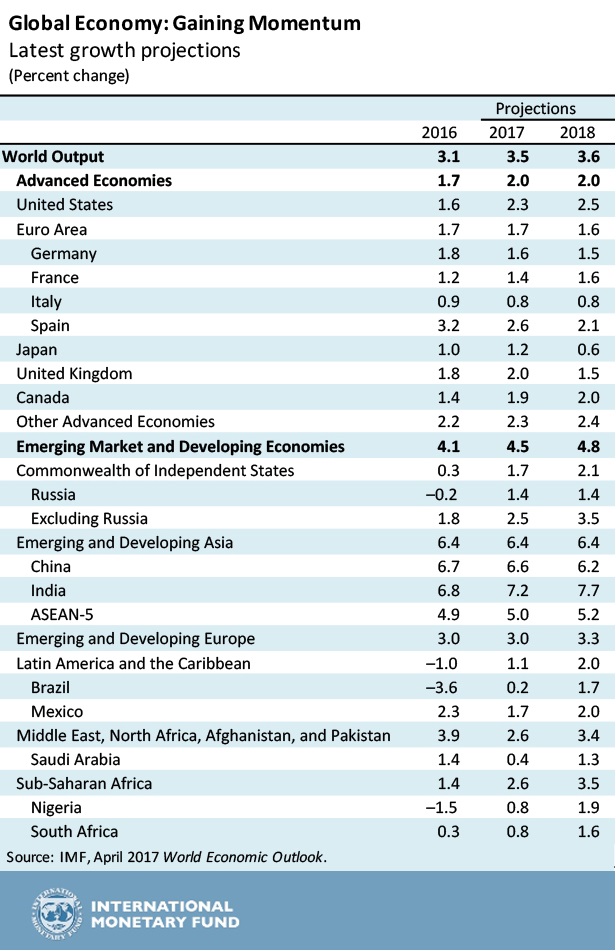

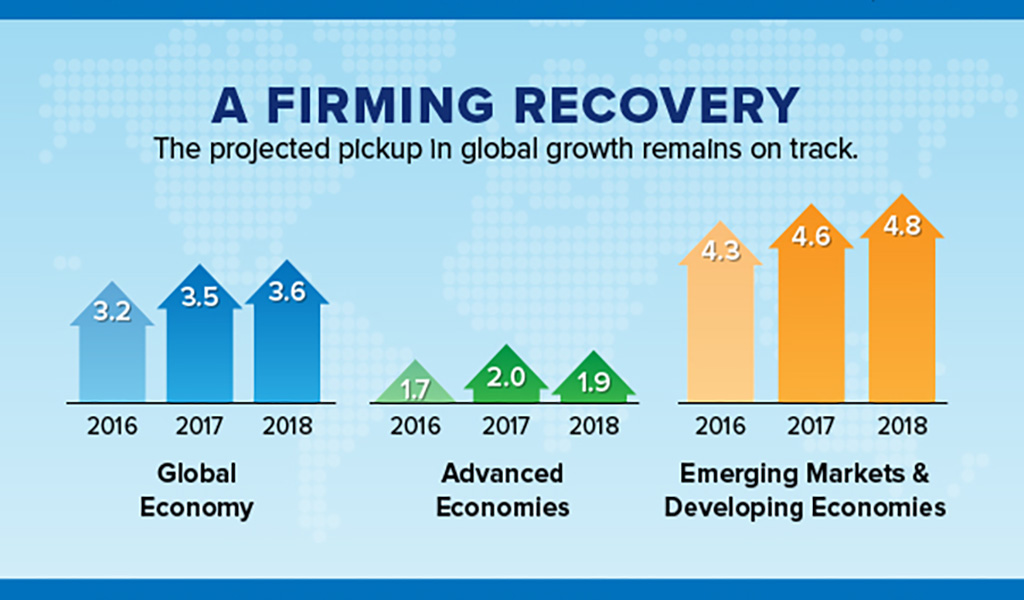

Momentum in the global economy has been building since the middle of last year, allowing us to reaffirm our earlier forecasts of higher global growth this year and next. We project the world economy to grow at a pace of 3.5 percent in 2017, up from 3.1 percent last year, and 3.6 percent in 2018. Acceleration will be broad based across advanced, emerging, and low-income economies, building on gains we have seen in both manufacturing and trade.

Our new projection for 2017 in the April World Economic Outlook is marginally higher than what we expected in our last update. This improvement comes primarily from good economic news for Europe and Asia, as well as our continuing expectation for higher growth this year in the United States.

Despite these signs of strength, many other countries will continue to struggle this year with growth rates significantly below past readings. Commodity prices have firmed since early 2016, but at low levels, and many commodity exporters remain challenged – notably in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America. At the same time, a combination of adverse weather conditions and civil unrest threaten several low-income countries with mass starvation. In Sub-Saharan Africa, income growth could fall slightly short of population growth, but not by nearly as much as last year.

Policy uncertainties and politics

Whether the current momentum will be sustained remains a question mark. There are clearly upside possibilities. Consumer and business confidence in advanced economies could rise further – though confidence indicators are already at relatively elevated levels. On the other hand, the world economy still faces headwinds. For one thing, trend productivity growth remains subdued across the world economy, for complex reasons that we have explored in a recent paper, and that seem likely to persist for some time. In addition, several prominent downside risks threaten our baseline forecast.

One set of uncertainties stems from macroeconomic policies in the two largest economies. The U.S. Federal Reserve has embarked on monetary normalization and may soon begin to scale back the size of its balance sheet. Given the faster U.S. recovery, we could see more upward pressure on the dollar, as interest-rate hikes are not yet imminent for the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank. At the same time, however, U.S. fiscal policy still seems likely to turn more expansionary over the next couple of years. If the slack remaining in the U.S. economy is small, the result could be inflation and a faster than expected pace of interest rate rises, reinforcing dollar strength and possibly causing difficulties for emerging and some developing economies—especially those with dollar pegs or extensive dollar-denominated liabilities. China’s desirable rebalancing process continues, as seen in a declining current account surplus and an increased GDP share of services, yet growth has remained reliant on domestic credit growth so rapid that it may cause financial stability problems down the road. These problems could, in turn, spill over to other countries.

Aside from the conjunctural policy uncertainties, a distinct set of threats comes from the growth in advanced economies of domestic political movements skeptical of international economic integration—no matter if integration is promoted through multilateral rules-based systems for the governance of trade, more ambitious regional arrangements such as the euro area and European Union, or globally agreed standards for financial regulation. A broad withdrawal from multilateralism could lead to such self-inflicted wounds as widespread protectionism or a competitive race to the bottom in financial oversight – a struggle of each against all that would leave all countries worse off.

Out of the woods?

So, the world economy may be gaining momentum, but we cannot be sure that we are out of the woods. How can countries safeguard and nurture the global recovery?

There is no universal policy prescription for diverse economies at different conjunctural stages. Deflationary pressures have generally receded, but monetary accommodation should continue where inflation remains stubbornly below target levels. Growth-friendly fiscal measures, especially where there is fiscal space, can support demand where that is still needed and contribute to expanding supply and reducing external imbalances. All countries have opportunities for structural reforms that can raise potential output as well as resilience to shocks, although specific reform priorities differ across economies.

Avoiding the damage from protectionist measures will require a renewed multilateral commitment to support trade, paired with national initiatives that can help workers adversely affected by a range of structural economic transformations including those due to trade. Trade has been an engine of growth, promoting impressive per capita income gains and declines in poverty throughout the world, especially in poorer countries. But its benefits have not always been equally shared within countries, and political support for trade will continue to erode unless governments step up to invest in their workforces and aid the adjustment to dislocations. Another recent paper of ours, co-authored with the World Bank and the World Trade Organization, surveys possible policy approaches. Importantly, such measures not only support trade, they aid adjustment to a range of structural changes—including those from rapid technology change. They can also raise potential output.

International cooperation key

International growth and stability rely on multilateral collaboration across a range of problems that spill over national borders--not just trade. The challenges include financial oversight, tax avoidance, climate, disease, refugee policy, and famine relief. Historically, inclusive cooperative approaches to interdependence have worked best. National policymakers, however, must do the hard work to ensure that the gains from harnessing interdependence, which are substantial, are broadly shared.

Read April 2017 World Economic Outlook

Listen: podcast